A “Baad” Story from Afghanistan

“We bought you with money and will kill you with a stone “Da zar kharidim da sang mekoshim”“

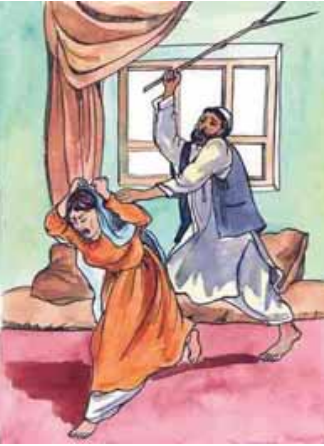

Violence against women and girls is a universal problem. The fear and sadness in a victim’s face is something I will never forget. I witnessed those faces in many countries, while working on “Rule of Law” projects, where we were trying to make the public aware that there were “legal” avenues to combat such an abuse. The recurring theme from the victims I met had an underlying commonality: the cold hatred in the eyes of the perpetrator, before and after the violent acts, was worse than the actual physical pain.

When I worked in a program involving the justice sector of Afghanistan, I learnt about “baad”. The New York Times had a story in 2012 that explained the baad custom that is prevalent in certain areas of Afghanistan.

It is a practice that most of us find repulsive: the giving of girls as reparation for the crimes or bad deeds of their male relatives. It is a traditional form of dispute resolution that had been made illegal in Afghanistan at the national level.

The Afghan Government in 2009 had enacted by decree, The Law on the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW), that specifically referred to the practice of baad, making it a criminal act to marry or “give away” girls and women to someone as blood price. The law prohibited the trading of women and girls to resolve disputes, including those related to murder, sexual violence, or other harmful acts. The UN’s Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA) had to say about baad in 2010 added this explanation to the problem:

“UNAMA HR found that giving away girls to settle disputes, through baad, takes place in communities throughout the country. In spite of the prevalence of this practice, many Afghans expressed strong opposition to it. As an informal method of dispute resolution, UNAMA HR found that in the central region more baad is practiced in conflict zones where the Government exercises less authority and lacks legitimacy (for example, conflict-affected areas such as Tagab and Alasay district in Kapisa province, Uzbin in Sarobi district of Kabul province) and in remote areas where the formal rule of law institutions are weakest.“

One reality, though, was that the formal justice sector outside of major urban areas had limited resources and functionality. At the local level, jirgas or shuras headed by community elders or religious leaders settled community disputes. Another reality was the fact that many communities were totally unaware of what the national law stated.

A booklet produced by the International Development Law Organization (IDLO), that was used by the Afghan Attorney General’s office to explain the EVAW, provided a glimpse of the enormity of the educational campaign needed to reach the many rural and remote provinces, communities and Government officials who did not know about the laws affecting the rights of women. There were other publications, as well as a comic book, Masooma’s Sunrise (see below). IDLO is a “global intergovernmental organization exclusively devoted to promoting the rule of law to advance peace and sustainable development”.

The U.S. military intervention in Afghanistan did not contemplate advancing women’s status and rights. However, the U.S. reconstruction effort’s goals included improving the lives of Afghan women and girls.

The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) found that from 2002 to 2020, the Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Department of Defense (DOD) disbursed at least $787.4 million for programs that specifically and primarily supported Afghan women and girls in the areas of health, education, political participation, access to justice, and economic participation. SIGAR also stated that “[t]his understates the total U.S. investment in women and girls, however, since hundreds of additional U.S. programs and projects included an unquantifiable gender component. State and USAID have not consistently tracked or quantified the amount of money disbursed for projects which directly or indirectly support Afghan women, girls, or gender equality goals. Therefore, the full extent of U.S. programming to support Afghan women and girls is not quantifiable.”

Nowadays, I find so little information about the plight of the women and girls in Afghanistan. So much time has gone by, and the little progress that had been made went up in smoke, so to speak, when the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan.

I look back at my involvement in the Rule of Law work we did in Afghanistan and can’t help thinking that we were neophytes in a social and legal experiment that we did not understand and were not fully committed to carry through.

One of my prized possessions is a lapis lazuli stone and a CD that the Afghan ladies working in the gender-based violence program I was involved with gave me. The CD contained pictures and recordings of the numerous billboards and TV programs that had been created to bring awareness to the population at large, and to let the victims of violence know that there were shelters available for them to seek protection and peace. A small amount of those millions of funds went into that campaign.

Nowadays, I can’t help but wonder, was all this for nought?